“Despite its global nature, the impacts of COVID-19 are not evenly distributed. The health, economic, social and political effects are hitting women harder across the globe, and across the African continent. It is time then to both understand and respond to this pandemic in a gendered way and to ensure that women lead the recovery efforts from the local to the national level.”

COVID-19, Gender, and a More Equitable Response for Sub-Saharan Africa

COVID-19 is truly a pandemic that knows no borders. The virus has caused over 110,000 deaths in the United States and over 200,000 cases across the African continent. And yet, despite its global nature, the impacts of COVID-19 are not evenly distributed. The health, economic, social and political effects are hitting women harder across the globe, and across the African continent. It is time then to both understand and respond to this pandemic in a gendered way and to ensure that women lead the recovery efforts from the local to the national level.

We are learning more every day and obtaining more data on how this disease affects all people, vulnerable communities and especially women. But we must keep in mind that the data are incomplete and often not disaggregated by sex or other socio economic factors. This, in and of itself, demonstrates how many communities and policymakers do not understand the disproportionate impact this pandemic is having on women.

There are, though, at least four distinct kinds of burdens women are facing during this pandemic.

The Health Burden

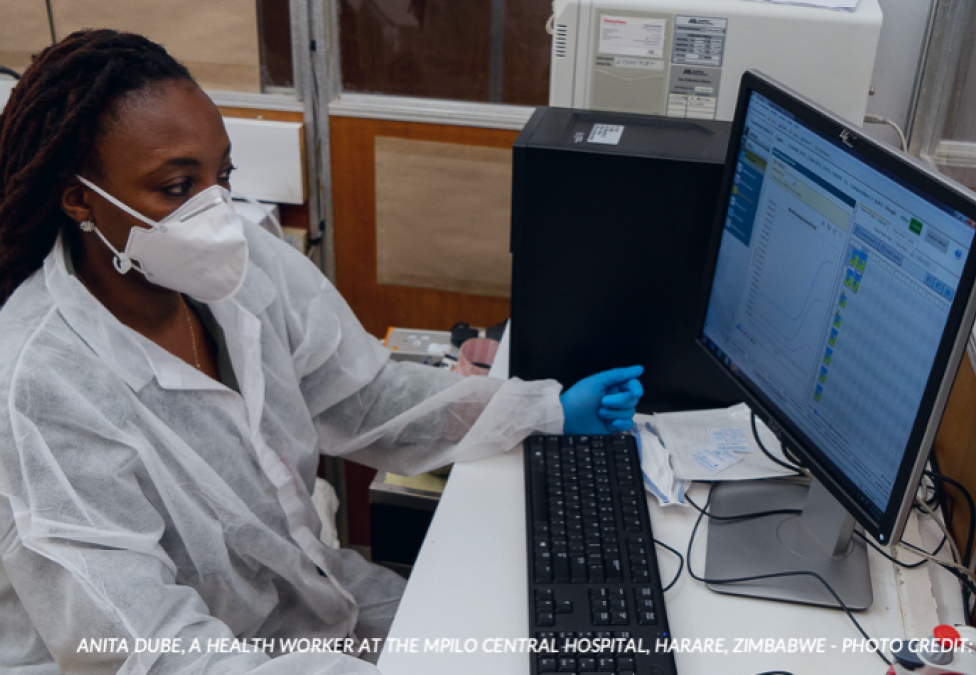

Women represent the majority of health and social workers who are in a high-risk category due to significantly higher exposure to the virus. Women comprise 70 percent of health and social care workers globally. The overall percentage of the health workforce that is women across the African continent is 60 percent, with women comprising approximately 90 percent of Egypt’s health workforce. On top of this, women are caregivers, and they also work in many front-line essential service industries from markets to food and beverage industries. Put simply, women are on the front lines. They are providing food, healthcare, and education to their families and communities – all activities that put them at risk during the pandemic.

The Economic Burden

The health impacts are exacerbated by the economic impacts caused by lockdowns and the global disruption of supply chains and trade. The sectors taking the hardest hit in terms of job losses are ones where women comprise over two-thirds of the employees: grocery, retail, tourism, beauty, and food and beverage. Across the continent, women also comprise 89 percent of the informal economy where lockdowns and health impacts have frequently resulted in business closures. These informal female workers are less protected by social safety nets and recovery plans that typically cover formal workers. Fatou Sow Sarr, who runs the gender research laboratory at the University Cheikh Anta Diop in Senegal, reports that 78 percent of women employed in informal enterprises in Senegal earn less than US$63 a month. It is exactly these women whose jobs are being lost and who do not have access to social safety nets or finance.

The Executive Director of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka has said it well: “This pandemic is hitting hard sectors where the majority of women are employed, and we know most women do not have savings. Therefore government and stakeholders should be keen on social protection and food security among other key issues in the gender responses of COVID-19.”

TheSocial Burden

COVID-19 has increased the time burden on women. Globally, women are caregivers: providing more than two and a half times more domestic work than men (from household chores to caring for children and elderly parents). With schools closed, women now have the additional burdens of having children at home all day. Many are also locked down with abusive spouses. And there are also the feelings of isolation. The impacts are felt in both mental and physical health problems.

The impacts on girls are also devastating. While on lockdown, they are missing opportunities to learn but also are at risk of abuse at home, health issues due to poor access to care, and an increased risk of entering into child marriage. Studies of past pandemics such as Ebola suggest that this type of emergency disrupts young girls and women’s pathways to education, economic independence and has adverse effects on girls’ health – as in many cases it is at school where young girls have access to information about sexual and reproductive health. According to Plan International at the end of March, around 743 million girls were out of school across the world. Many may never return to class.

On top of school closures, only 27 percent of women in Africa have access to the internet and only 15 percent of them can actually afford the cost to use the internet. In places like Mali, Malawi, and Niger, less than 10 percent of women have regular access to the internet. The result is that girls and women are left “offline” – including cell phones – and thus isolated from education, information, and social engagement.

The Political Burden

Finally, across the continent women comprise between 23 and 27 percent of the government workforce. The impact is that many decisions about recovery and policy decisions may be made without considering the needs of women and girls, and without their experience. The result will be that the needs of the entire community will not be met, and full socio-economic recovery will be more difficult. The end result is pulling certain communities and countries back into poverty. As UN Women’s Mlambo-Ngcuka has warned, “We know from Ebola experiences when you exclude women you are likely to face a catastrophe.”

What Should be Done?

The first step in designing effective recovery processes and programming is to disaggregate data by sex, age, and disability. This, clearly, should include data related to the impacts of COVID-19 and the implementation of emergency responses. Globally, there is inconsistency in the collection, disaggregation, and reporting of data for adolescent girls and young women. Without credible and consistent data, governments and emergency responders are constrained in their ability to understand the gendered differences in exposure, impact, and treatment and to design differential preventive measures and responses.

Next, policymakers should design recovery efforts with gender equality in mind. Policies should encourage employers to allow for more flexible, predictable remote work, and should take into account issues of transportation, time burden, and access to technology. Bailout packages that focus on formal and informal employment are key, and this can include programs to support women in tech and provide financing for women-owned businesses. Interventions should also address the unequal burden of unpaid care and domestic work on girls and women. One step is for fathers to pick up more care of childcare and housework and for all programs from education to finance to keep gendered norms in mind. Finally, there must be both a gender lens and gender balance in decision-making.

The premise behind all of this is that effective socio-economic recovery requires attention to equity and addressing the needs of all members of society starting with women who make up 50.4 percent of the population globally. Recovery efforts can – and should – understand, analyze, and address inequity. The result will be that the policies be will be more successful in the short and long-term, and also that the trust between government, businesses, and citizens will be restored and act as the basis for a strong recovery: one that benefits the entire community.