“We look at mobility data from Google to see how effective four East African countries have been in reducing social interaction in line with the kind of suppression strategies health experts were recommending at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Introduction

In one of the landmark early studies on COVID-19, researchers from the Imperial College London (ICL) estimated that “in the absence of interventions, COVID-19 would have resulted in 7.0 billion infections and 40 million deaths globally this year.” Their analysis recommended a “suppression” strategy of strict social distancing of the kind that has become familiar across the globe. According to their model, a “75% reduction in interpersonal contact rates,” combined with testing and contract tracing, could reduce the number of infections in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) from 1.0 billion, in an unmitigated scenario, to 110 million.

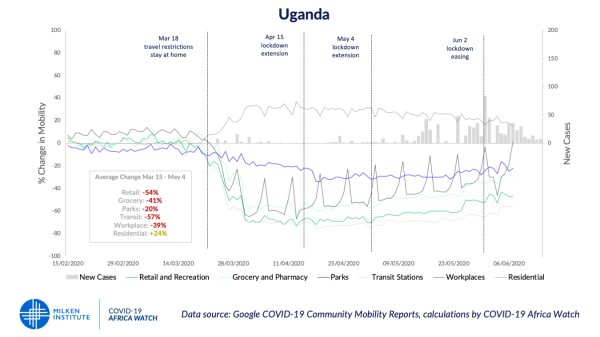

In this piece, we look at mobility data from Google to see how effective four East African countries have been in reducing social interaction in line with the kind of suppression strategy ICL researchers and others were recommending at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The countries we examine – Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania – present varied policy approaches (and varied health outcomes), and so allow us to arrive at some early, caveated takeaways.

We’ll start with the caveats.

The first is this. The data here come from Google’s ‘Community Mobility Reports’ which “are created with aggregated, anonymized sets of data from users who have turned on the Location History setting” on their Google products. This sample of internet and smartphone users may be an imperfect proxy for the wider populations in East Africa. Internet penetration in our target countries is as follows: 87% in Kenya, 46% in Rwanda, 39% in Tanzania, and 40% in Uganda. Smartphone usage is less common in all four countries. As a result, the mobility data here may only provide a window into an online, more prosperous segment of the population in each country, with imprecise implications for offline, poorer workers in the informal economy.

Our second caveat is that the health impacts of COVID-19 are still unfolding around the world and in these four countries. It is likely too early to pronounce success or failure, particularly as ongoing outbreaks seem inevitable. Still, we think at least four initial takeaways are possible.

But first let’s look at the data. Use the tabs below to see graphs for each country, as well as a summary for the region.

COVID-19 mobility data for East Africa

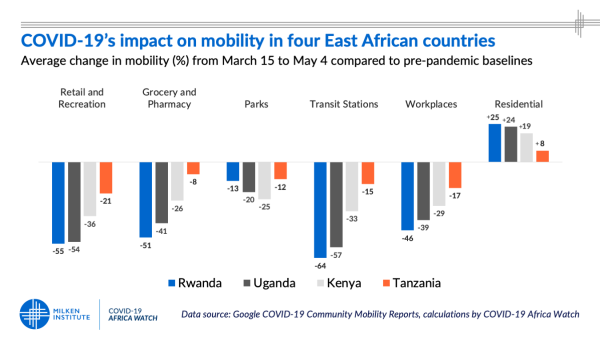

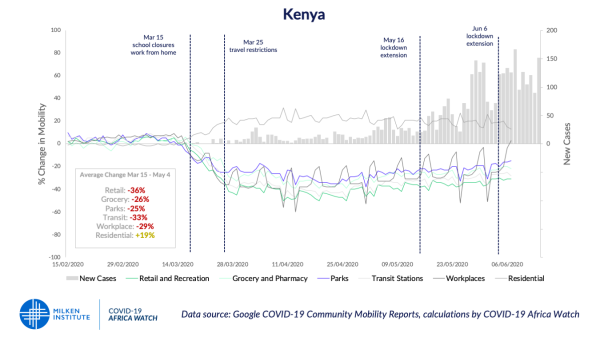

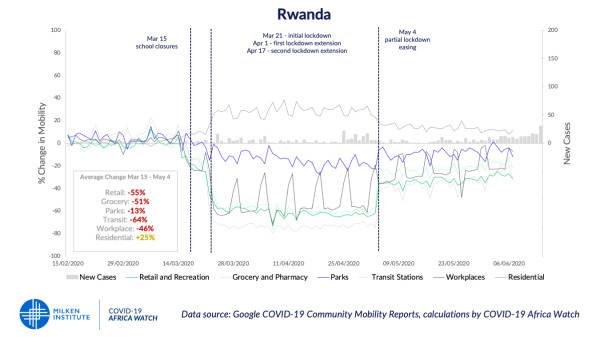

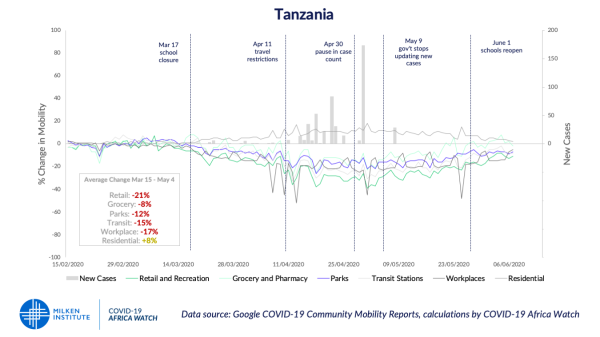

The graphs above show mobility data for travel to six kinds of destinations: grocery and pharmacy, parks, transit stations, retail and recreation, residential, and workplaces. The data are graphed from February 15 (the day after Africa’s first case was confirmed in Egypt) to June 12, 2020. The percent changes in mobility are based on a pre-COVID-19 baseline of activity, comprised of averages from the 5‑week period from January 3, to February 6, 2020. (To illustrate, mobility trend figures for April 30 (Monday) are changes vs the median of January 6, 13, 20, 27, and February 3 mobility values.) The gray vertical bars show new confirmed cases on each day. We also added the dotted vertical lines to show significant policy decisions made by each government.

To interact with the data, visit our ShinyApp visualization here.

Initial takeaways

As we said above, we think there are four initial takeaways from these graphs.

1. Social distancing policies work at reducing mobility.

Reductions in mobility coincide almost exactly with policy announcements across all four countries. From school closures to full lockdowns, policy decisions – and enforcement – clearly impacted mobility in line with the recommendations of health experts to limit social interactions.

2. Stricter lockdowns reduce mobility more than partial lockdowns.

As above, this point may seem like common sense, but it is worth emphasizing nonetheless. Rwanda and Uganda both implemented strict, stay-at-home-style lockdowns, and in both countries, mobility fell dramatically. These countries have also had the most success in containing the spread of COVID-19 in the East African region.

Kenya implemented more limited restrictions initially, and then later expanded restrictions on movements, but only in major cities. There, mobility has dropped, but not as much as in Rwanda and Uganda. In Tanzania – where the government stopped releasing new official case figures on May 9 and is, in many instances, denying the reality of the virus altogether – mobility still responded to the policy decision to close schools. The drop, though, was far less than where governments implemented more restrictive measures. The East Africa summary tab above makes this clear.

3. When lockdowns end, mobility initially remains lower than pre-COVID-19 baselines.

The cases of Rwanda and Uganda show that populations continue to move at below baseline levels even after lockdown policies are ended. Travel to transit stations, retail sites, and grocery stores, in particular, remains suppressed, a fact that likely has implications for the economic recovery. Even in Tanzania, people are moving less than they did before the pandemic started. More research should be done on why this is happening. One idea is that populations are responding to a better understanding of how the virus spreads, and its dangers. And as such, mobility figures may remain below pre-pandemic levels until all active cases have become recoveries, which is something only a handful of countries globally have achieved.

4. Lockdowns appear to buy time, but there may be limits to how long they remain effective.

Kenya’s case shows this point most clearly. Mitigation efforts appear to have given the country about two months to prepare for an outbreak. But the outbreak did eventually begin, even as lockdown measures were extended once and then again. Likewise, in Rwanda and Uganda, lockdowns successfully contained the virus, but new cases begin to rise later despite this early success. These findings actually underscore the danger of Tanzania’s approach. Just as lockdowns do not make COVID-19 any less infectious once they end, neither does failing to report cases change the infectious nature of the virus.

Final thoughts

With just over 250,000 total cases at present (in all of Africa, not just SSA), it appears the continent will outperform even the best of the best-case suppression models envisioned by the ICL team in their March report, back when 110 million cases seemed optimistic. This outcome is certainly due to early policy measures undertaken by many proactive governments across the continent. It is an exceptional achievement, one that should be broadcast widely and applauded, even as ongoing vigilance is required.

While the data above indicate how effective some policy measures have been so far, we believe there is much more that researchers and policymakers can and should do with these data. One of our hopes in writing this piece is that others will take this kind of analysis forward and go far beyond what we have done here, expanding to addition countries and also introducing new variables into the analysis. A possible angle of interest would be to use these data to assess the economic impact of lower mobility and how mobility increases track renewed economic activity once the recovery story develops.

COVID-19 Africa Watch tracks major developments and policy announcements from across the continent and also offers a curated selection of analysis on how the pandemic will impact African economies and development efforts. The site is a project of the Milken Institute’s Global Market Development Practice.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of COVID-19 Africa Watch or any affiliated organization.