|

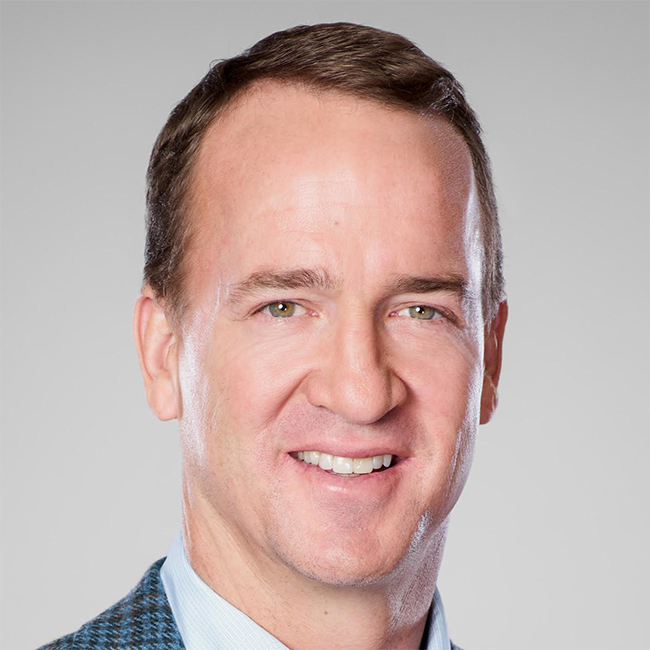

Q & A with Elijah HutchinsonVice President of Waterfronts, New York City Economic Development Corporation |

Jason Davis: You hold an important and unique role at the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC). What attracted you to this work, and what are some of your core responsibilities?

Elijah Hutchinson: I see climate change as the greatest threat facing 21st-century cities. We have spent decades making stronger connections to our waterfront, and now that very same waterfront could pose extreme risks to communities. I focus on facilitating long-term planning and redevelopment projects on New York City’s waterfront, inclusive of infrastructure, open space, and mix-used developments. Current project highlights include Lower Manhattan Coastal Resilience, the City’s plan to adapt Lower Manhattan to climate change for this generation and the next. It consists of the City’s first comprehensive climate risk assessment, funding for over $800 million in capital projects, and a climate resilience master plan. The master plan examines creating new land off the Financial District and Seaport shorelines to help protect NYC and the region from the effects of rising seas and climate change. In addition, we broadly advise across the Corporation’s portfolio to ensure we are making the wisest investments with the best climate and risk information we have.

How do you measure success at NYCEDC, and are there any projects you have worked on that were particularly impactful and personally rewarding?

Success is taking broad, long-term visions and turning them into implementable projects through strategy development, design, technical analysis, inter-agency and community engagement. In the world of long-term planning, it can sometimes take over a decade or more to see a shovel in the ground. Recently, I was excited to see the hip hop museum in the Bronx start construction, affordable housing rise in downtown Far Rockaway, and an over $700 million investment being made by the mayor this spring to complete the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway loop. Most greenway gaps exist in historically under-served neighborhoods in northern Manhattan and Harlem. One gap in the greenway from East 60th to 53rd Street is being constructed now as an over-water bridge parallel to the existing shoreline in the East River—it’s a real testament to how creative one needs to be to find solutions to our complex waterfront planning problems.

Can you outline some of the most pressing climate-change-related challenges NYC’s water-adjacent communities face? How is NYCEDC working to improve neighborhood resilience?

New York City's coastline stretches 520 miles and is longer than the coastlines of Miami, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco combined. On our shores is a mix of neighborhoods old and new, some dense and some sparse, representing a range of incomes and uses that reflect the diversity of our city. As we think through an economic recovery for New York City, we cannot forget about climate change and reducing risk to crucial neighborhoods that include a dense concentration of jobs, critical infrastructure, vital city-owned assets, and transportation resources. Because every neighborhood is unique with its own waterfront characteristics and facing specific climate risks, infrastructure solutions in each respective neighborhood will end up looking different—sometimes an elevated park, or flood gates, or new land, or elevating streets, or coastal berms, etc. NYCEDC, with our long legacy of waterfront asset management and capital project development, brings together community priorities with the latest climate science. We use forward-thinking technologies and global precedents to identify the best set of project options that meet our collective resilience goals. For example, this approach resulted in neighborhood-scale resilience projects in Red Hook, Coney Island, Hunts Point, the Rockaways, and Lower Manhattan.

Addressing coastal flooding and other risks faced by communities across New York’s five boroughs is a massive undertaking, with resilience projects that take many years to complete and cost significant amounts of money. Why is it important that diverse stakeholders come together to address these challenges head-on?

Superstorm Sandy brought $47 billion in damages and $26 billion in lost economic output region-wide. In the three days following Sandy, the region experienced an estimated $16 billion in decline in the production of goods and services. With sea levels projected to rise in New York City by about 2.5 feet within the life of a 30-year mortgage that you would get today, and by approximately 6 feet by 2100, more areas of New York are vulnerable to flooding from daily high-tides, coastal storms, and rainfall events. And the costs of mitigating these impacts are enormous, but one dollar spent on resilience can be a dollar well spent because of the benefit that one dollar confers. These public investments make sense and often require a positive cost-benefit analysis calculation to unlock critical funding from our State and Federal partners. There are also other difficult to quantify benefits to being a resilient community that are more clearly understood when connecting with community stakeholders, local experts, and related advocates. We also know that NYC is a very connected city through our complex urban infrastructure systems like transportation, drainage, and sewers. Hunts Point losing power means compromised food distribution for the entire City. Lower Manhattan has 75 percent of our subway lines passing through it and the hub for the whole NYC Ferry network connecting all five boroughs. A coalition that intersects across these interests is most effective for ensuring continued advocacy and funding for coastal infrastructure projects.

As the City explores coastal resilience infrastructure solutions, how do you incorporate community input and equity into the design process?

Communities across New York City are beyond having isolated opportunities to give “input” into critical infrastructure projects that can dramatically reshape their relationship to their waterfront, access to transportation, and general well-being and safety. I have heard that people want an opportunity to co-create designs, have engaging and educational outreach events, have transparency in technical analysis, and have shared decision-making opportunities. It is critical to think through who will benefit from these projects and if the waterfront is truly accessible to a diversity of users, as well as to be clear about how these projects may impact communities through construction and ongoing maintenance and operations. Building relationships with communities, being responsive to concerns, being reflective in our planning practice, and re-evaluating our approaches will lead to better outcomes for both the community and the City over time.

NYCEDC collaborated with the Milken Institute on a Financial Innovations Lab in 2019 that explored funding and financing options for coastal resilience infrastructure projects in Lower Manhattan. In the years since, how have the ideas explored during the Lab helped inform your subsequent work?

Collaborating with the Milken Institute was an excellent opportunity to bring together industry professionals and local stakeholders to explore various funding and financing options to advance resilience projects. Thinking about how to solve this problem for Lower Manhattan means identifying potential solutions that could benefit other parts of New York City because of the range in possible frameworks for how costs and benefits could be distributed. We discussed how a “resilience district” might work or how much money you could really get from a water and sewer surcharge, for example. This discussion allowed us to better understand that not one funding source would be a silver bullet. A range of funding strategies will be needed for any project while often requiring significant public contributions from the City, State, and Federal governments. From a financial analysis perspective, we also got to explore what role potential residential or commercial development might play in our project and the limitations of relying on private development. As we develop the concept design for a new 21st-century waterfront in the Financial District and Seaport, we continue to build off these partnerships to advance our financial analysis and collect critical stakeholder feedback.

As you consider the next decade in NYC, what does a successful implementation of the City’s resilience strategy look like for waterfront communities?

A resilience strategy is more than coastal protection projects. It’s about land-use, building codes, hardening utilities, improved community and emergency action protocols, increasing social resilience, having (and sharing!) data, and layers of protection at multiple scales from businesses having resilient data networks and buildings being retrofitted to having neighborhood-scale coastal protection projects that reflect community priorities. Developing a resilience strategy will be a continuous process of physical and social adaptation for decades to come to respond to the new realities of a changing climate. My hope is that we will take these opportunities to design for a more equitable City, with newly accessible waterfront areas, more resilient transportation connections, and opportunities to learn about maritime and ecological issues. Importantly, I hope that we develop projects that provide engaging public spaces that will serve future New Yorkers who will experience climate change impacts in ways that we are only beginning to understand.

The views expressed here are those of Elijah Hutchinson and not the views of NYCEDC or the City of New York.