Community health workers (CHWs), also known as promotoras, community health navigators, and lay health workers, have been utilized in the US since the 1950s; however, their emergence onto the health-care scene, especially in under-resourced and disenfranchised communities, began in the 1990s, as reported in the Annual Review of Public Health. Now integrated into the health-care system, these workers are trusted care extenders, as discussed in the American Journal of Public Health, as they often come from or have a deep understanding of the communities they serve, communities disproportionately affected by health disparities and inequities. Although their visibility increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and extensive evidence supporting their contributions to health outcomes fills the biomedical and public health literature, they remain underutilized, according to studies in Health Education & Behavior and Preventive Medicine Reports.

CHWs function in a variety of settings, including local and state health departments, community-based organizations, health-care and health-insurance organizations, and federal agencies, as examined in Health Affairs and JAMA Internal Medicine. These health-care extenders can serve in many roles, including as health educators and advocates, as well as assisting in pandemic emergency responses. From facilitating health-care access through care navigation to demystifying health procedures and testing, CHWs are also vital for addressing social needs, including ever-increasing gaps in the social determinants of health (SDOH), among others, which are unseen by other members of the health-care team. This package of care CHWs provide makes them effective across a wide spectrum of diseases and conditions, according to a study in Population Health Management.

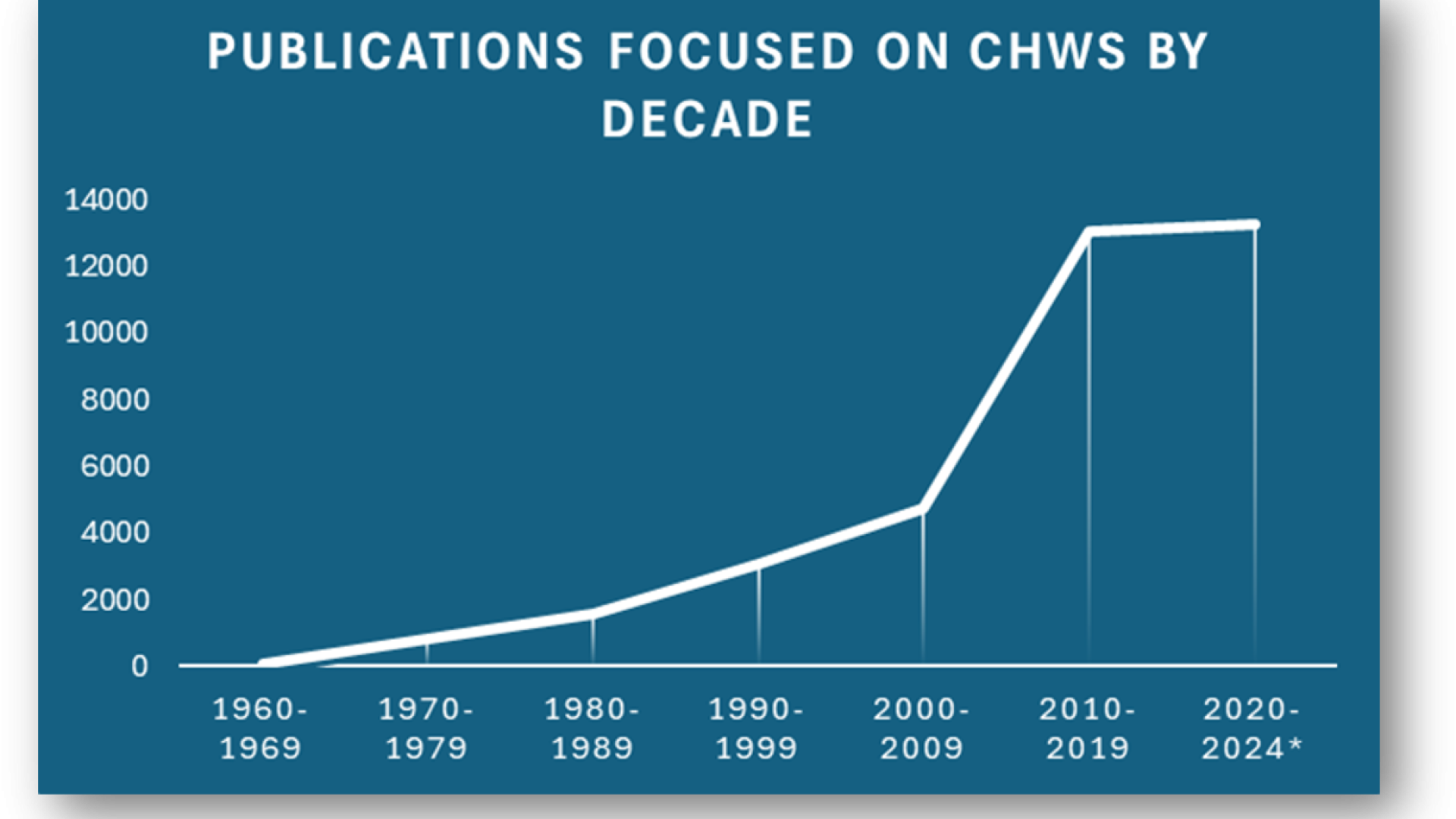

Their expansion across the care spectrum is mirrored by the increase in publications in the scientific literature about their role, utility, and effectiveness. The figure below depicts an analysis of the number of publications that reference CHWs by decade since the 1960s, demonstrating a 14,821 percent increase.

Source: Authors’ analysis utilizing PubMed Search Engine for CHW-focused publications retrieval by decade 1960–September 20, 2024 (Milken Institute 2024)

As the number of publications expanded, the topics reflected the growing shift in the role of CHWs and their place in health-care teams. In the first decade, one-third of the publications retrieved had little to do with CHWs and focused more on community approaches to health management. By the 1990–2000 period, the publications not only identified the scope and role of the CHWs but also reflected their place globally in health care and across specialties. During this decade, the American Journal of Public Health called them “…integral members of the healthcare workforce.” By 2010, the literature pointed to the potential role of CHWs in research recruitment and retention, as well as a value-add in social work. From 2020 to 2024, publications about CHWs nearly equaled those of the prior decade, confirming ongoing proliferation of research into CHW roles and return on investment.

Today, CHWs are not only effective across many conditions and settings, but the challenge of codifying their effectiveness has lessened with an increasing number of randomized clinical trials and disease-agnostic studies. CHWs clearly provide benefits across many conditions—including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, HIV, maternal health, and multiple comorbidities. Their work results in a decrease in emergency room visits and bolsters social support among diverse populations, including Latinos, African Americans, Native Americans, lower socioeconomic status individuals, and more, as explored in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved.

Why Aren’t CHWs Utilized More?

In 2010, through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the growth of value-based payment, the expansion of CHW programs accelerated within health care. By all estimates, CHW numbers and programs are expected to increase through 2029 due to the funding from the American Rescue Plan and the ongoing need to bolster an already overburdened health-care system, as discussed in the Journal of Health, Politics, Policy and Law. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, as of January 2024, 15 states and the District of Columbia utilize the Medicaid state plan amendments to reimburse CHW services. A bipartisan bill, the Community Health Worker Access Act, will improve local health workers’ ability to bridge gaps in health outcomes by improving Medicare coverage for their services, including personalized support for illness prevention and recovery. However, this bill would limit the expanded access to CHW services to those on Medicare and Medicaid only.

According to the US Census Bureau, in 2022, private health insurance coverage continued to be more prevalent than public coverage, at 65.6 percent versus 36.1 percent. This means two-thirds of the US population would not have access to the cost-effective services of a CHW because of lack of reimbursement. As reported in JAMA, at a time when the US spends between $421 billion and $450 billion annually due to health disparities and differential outcomes, limited reimbursement for the services of these trusted health-care workers will yield worse health and economic outcomes for individuals and society.

CHWs have shared with the authors what they do and what it means to the people they serve. Priscilla Koilor, founding director of Mobile Holistic Healing Services, notes, “When the patient is discharged from the emergency department with a prescription for insulin, it is the CHW, not the physician, who finds that there is no food and no refrigerator for the patient, making the storage of insulin, let alone its use, neither feasible nor safe.” A published photo essay of Baltimore CHWs in Health Affairs points out the challenges faced and the additional stress they place upon the workers: “… a concern that all CHWs share, [is]not only with funds for direct services, such as food, but also for our jobs, which are paid with specific funds and are not permanent. When funds are low, they make cuts, which, unfortunately, may be [of] what is needed the most.”

The reality is that CHWs often experience the very disparities they are tasked to address. Members of vulnerable communities themselves, they also struggle to effect change and improve outcomes while facing challenging work conditions, job insecurity, and uncertain wages. Yet, CHWs are among the interventions demonstrated to address disparities and be cost-effective and efficient.

What Is Lacking?

Barriers to exploring and scaling up effective CHW models like Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT), a standardized community health worker intervention that addresses socioeconomic and behavioral barriers to health in low-income populations discussed in Health Affairs, must be identified and addressed, as well as the ongoing challenges to expanding CHW reimbursement. At the same time, it will be essential to monitor return on investment and reinvest dollars saved to further decrease SDOH that confound health disparities and health outcomes, which are explored in the Annual Review of Public Health and the National Academies reports. The Milken Institute remains focused on the drivers of health inequity and the opportunities to highlight and remediate them. Informing this activity with the voices and lived experiences of those affected by these inequities remains central to this mission.